Individuals, organizations, and institutions frequently face social dilemmas that pit their short-term interests against what is best for the greater good in the long run. Recognizing and successfully navigating these social dilemmas requires sound moral decision-making.

In the moral learning project, we found that how people make moral decisions is highly malleable to learning from experience (Maier, Cheung, & Lieder, 2024). In the reflective learning project, we found that learning from experience can be accelerated and enhanced through systematic reflection (Becker, et al., 2023). Therefore, promoting moral learning through systematic reflection might be a promising approach to positively impacting the numerous small and large decisions that jointly determine the future of humanity.

This project aims to understand whether and, if so, how moral learning can be boosted by engaging people in systematic metacognitive reflection about their moral decision-making and its consequences. If successful, this project might lead to a chatbot for fostering moral growth, promoting ethical leadership, improving institutional decision-making, and giving young people and future generations a better moral education.

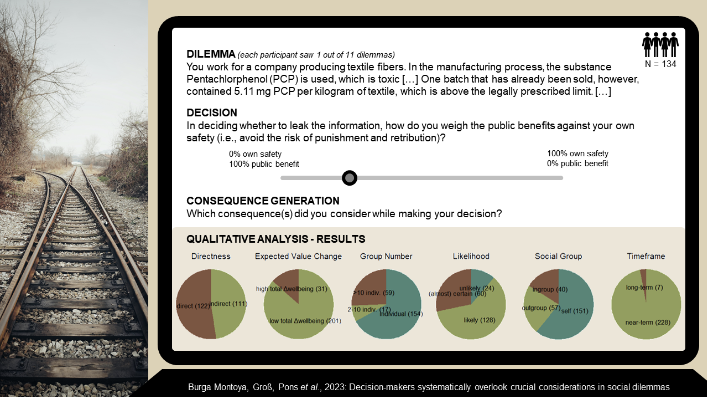

To be able to effectively improve people’s moral decision-making through reflection, we first need to know about people’s natural decision-making and the biases compromising their decisions in social dilemmas. We designed social dilemmas where the participants make decisions about sharing resources (e.g. time or money) between themselves or those close to them (egocentric decision, e.g. one’s employees) and distant others (altruistic decision, e.g. employees of another company or people in a far country). After participants make a decision, we ask them what consequences they considered when thinking about the dilemma and how important each of those consequences was for them.

We hypothesized that when making decisions in social dilemmas, people systematically overlook morally significant long-term consequences for distant others and tend to give a disproportionate amount of weight to short-term consequences. As expected, our preliminary analysis suggested that people are not as altruistic as they could be. Compared to the most altruistic option, people’s average altruism score was 41.32%. Taking a closer look at which consequences they considered revealed that a majority were about individuals (66%) and the near future (97%). This is striking because increasing the well-being of many people for a long time requires considering the long-term consequences for large groups of people, which is the exact opposite of what our participants focussed on.